|

Latar belakang

Isu perkauman dalam pilihan raya 1969

Semasa kempen Pilihan Raya 1969, calon-calon pilihan raya serta ahli-ahli politik dari kalangan parti pembangkang, telah membangkitkan soal-soal Bangsa Malaysia berkaitan dengan Bahasa Kebangsaan (Bahasa Melayu), kedudukan istimewa orang Melayu sebagai (Bumiputera) dan hak kerakyatan orang bukan Melayu. Hal ini telah memberi kesempatan kepada ahli-ahli politik yang ingin mendapatkan faedah dalam pilihanraya.Pada pilihanraya umum 1969Parti Perikatan yang dianggotai oleh (UMNO-MCA-MIC) telah gagal memperolehi majoriti 2/3 diparlimen, walaupun masih berjaya membentuk kerajaan persekutuan. Hal ini disifatkan oleh parti pembangkang sebagai satu kemenangan yang besar buat mereka. Jumlah kerusi yang dimenanginya dalam Dewan Rakyat (Parlimen) telah menurun daripada 89 kerusi pada tahun 1964 kepada 66 kerusi pada tahun 1969.

Parti Gerakan Rakyat Malaysia (Gerakan), Parti Tindakan Demokratik (DAP) dan Parti Progresif Rakyat (PPP) menang 25 buah kerusi dalam Dewan Rakyat manakala PAS menang 12 kerusi.

Pihak pembangkang yang memperoleh pencapaian gemilang dalam pilihanraya telah meraikan kemenangan mereka pada 11 Mei 1969. Perarakan tersebut sebenarnya tidak bermotif untuk menimbulkan isu perkauman. Malah terdapat segelintir pengikut perarakan (identiti mereka tidak dapat diketahui) telah mengeluarkan slogan-slogan sensitif berkenaan isu perkauman semasa mengadakan perarakan di jalan-jalan raya di sekitar Kuala Lumpur. Perarakan turut dijalankan pada 12 Mei 1969 di mana kaum Cina berarak menerusi kawasan Melayu, melontar penghinaan sehingga mendorong kepada kejadian tersebut.[1]. Pihak pembangkang yang sebahagian besar darinya kaum Cina dari Democratic Action Party dan Gerakan yang menang, mendapatkan permit polis bagi perarakan kemenangan melalui jalan yang ditetapkan di Kuala Lumpur. Bagaimanapun perarakan melencong dari laluan yang ditetapkan dan melalui kawasan Melayu Kampung Baru, menyorak penduduk di situ.[2] Sesetengah penunjuk perasaan membawa penyapu, kemudiannya dikatakan sebagai simbol menyapu keluar orang Melayu dari Kuala Lumpur, sementara yang lain meneriak slogan mengenai tengelamnya kapal Perikatan — the coalition's logo.[3] Ia berlarutan hingga ke 13 Mei 1969 sebelum Parti Gerakan mengeluarkan kenyataan meminta maaf pada 13 May di atas kelakuan penyokong mereka. Menteri besar Selangor, Dato' Harun Idris telah mengumumkan bahawa perarakan balas meraikan kemenangan UMNO akan dijalankan pada pukul 7.30 malam, 13 Mei 1969.

Pembangkang meraikan kemenangan

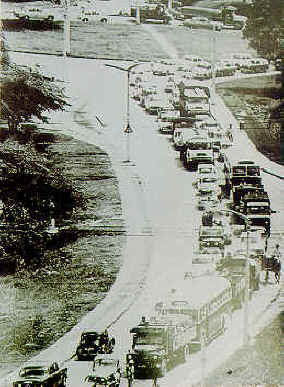

Peristiwa ini berlaku berikutan pengumuman keputusan Pilihanraya Umum pada 10 Mei 1969.Dr. Tan Chee Khoon dari parti Gerakan telah menang besar di kawasan Batu, Selangor. Beliau minta kebenaran polis untuk berarak meraikan kemenangan parti tersebut di Selangor yang menyaksikan 50:50 di Selangor. Perarakan tersebut menyebabkan kesesakan jalan raya di sekitar Kuala Lumpur. Perarakan hingga ke Jalan Campbell dan Jalan Hale dan menuju ke Kampung Baru. Sedangkan di Kampung Baru, diduduki lebih 30,000 orang Melayu yang menjadi kubu UMNO, berasa terancam dengan kemenangan pihak pembangkang. Di sini letaknya rumah Menteri Besar Selangor ketika itu, Dato' Harun Idris.

Dikatakan kaum Cina yang menang telah berarak dengan mengikat penyapu kepada kenderaan mereka sebagai lambang kemenangan mereka menyapu bersih kerusi sambil melaungkan slogan. Ada pula pendapat yang mengatakan penyapu tersebut sebagai lambang mereka akan menyapu ('menyingkir') orang-orang Melayu ke laut. Dalam masyarakat Melayu, penyapu mempunyai konotasi yang negatif (sial). Ada yang mencaci dan meludah dari atas lori ke arah orang Melayu di tepi-tepi jalan.

Perarakan kematian Cina

Di Jinjang, Kepong, kematian seorang Cina akibat sakit tua diarak sepanjang jalan dengan kebenaran polis. Namun perarakan kematian bertukar menjadi perarakan kemenangan pilihan raya dengan menghina Melayu.Pada hari Selasa 13 Mei, Yeoh Tech Chye selaku Presiden Gerakan memohon maaf di atas ketelanjuran ahli-ahlinya melakukan kebiadapan semasa perarakan. Yeoh menang besar di kawasan Bukit Bintang, Kuala Lumpur. Tapi permohonan maaf sudah terlambat.

Rumah Menteri Besar Selangor

UMNO telah mengadakan perarakan balas pada pagi 13 Mei 1969 yang mengakibatkan terjadinya peristiwa ini. Hal ini adalah kerana perasaan emosi yang tinggi dan kurangnya kawalan dari kedua-dua pihak. Perarakan ini tidak dirancang.Orang Melayu berkumpul di rumah Menteri Besar Selangor di Jalan Raja Muda Abdul Aziz di Kampung Baru, Kuala Lumpur. Dato' Harun Idris selaku Menteri Besar Selangor ketika itu cuba mententeramkan keadaan. Rupa-rupanya, mereka yang berkumpul telah membawa senjata pedang dan parang panjang dan hanya menunggu arahan daripada Dato' Harun Idris untuk mengamuk. [perlu rujukan]

Ketika berkumpul, cerita-cerita tentang kebiadapan ahli parti Gerakan tersebar dan meluap-luap. Jam 3.00 petang datang berita kejadian pembunuhan orang Melayu di Setapak, hanya dua kilometer dari rumah Menteri Besar Selangor. Terdapat cerita-cerita lain mengenai seorang wanita mengandung dibunuh dan kandungannya dikeluarkan dari perut dengan menggunakan besi penggantung daging babi.Sebelum menghembuskan nafas terakhir wanita tersebut sempat memasukkan semula janin yang terkeluar itu ke dalam perutnya.

4.00 petang dua penunggang motosikal Cina yang melalui Jalan Kampung Baru telah dipancung. Sebuah van membawa rokok dibakar dan pemandunya dibunuh. Pemuda-pemuda Cina yang dikatakan dari PKM dan kongsi-kongsi gelap telah bertindak balas. Mereka membunuh orang-orang Melayu di sekitar Kuala Lumpur. Rupa-rupanya orang Cina dan pemuda Cina ini lengkap dengan pelbagai senjata besi, tombak dan lembing berparang di hujung seperti dalam filem lama Cina.

Cerita-cerita seperti ini yang tidak diketahui sama ada benar atau tidak telah menyemarakkan lagi api permusuhan di antara Melayu dan Cina. Rusuhan besar terjadi. Perintah darurat dikeluarkan, semua orang tidak dibenarkan keluar dari rumah. Pasukan polis berkawal di sekitar Kuala Lumpur. Tentera dari Rejimen Renjer lebih awal dikerahkan menjaga keselamatan sekitar Kuala Lumpur.

Rejimen Renjer

Pasukan FRU di keluarkan dari Kampung Baru dan askar dari Rejimen Renjer ambil alih. Malangnya pasukan ini terdiri dari orang-orang Melayu, Iban, Cina, India, Sikh, Gurkha dan lain-lain turut menembak orang-orang Melayu dan ini menyebabkan kemarahan orang Melayu semakin meluap-luap. Menurut laporan, ketua pasukan Rejimen Renjer dikatakan berbangsa Cina.Pemuda-pemuda Melayu yang mempertahankan Kampung Baru dan yang lain-lain mengamuk merasakan diri mereka terkepung antara orang Cina dengan askar Rejimen Renjer. Beberapa das turut ditujukan ke arah rumah Menteri Besar Selangor.

Askar Melayu

Akhirnya Regimen Renjer dikeluarkan dan digantikan dengan Askar Melayu. Beberapa bangunan rumah kedai di sekitar Kampung Baru, Jalan Tuanku Abdul Rahman masih terus terbakar. Pentadbiran diambil-alih oleh Askar Melayu. Malangnya beberapa askar Askar Melayu turut masuk ke kedai-kedai emas Cina dan mengambil harta benda di sana. Malah ada askar melayu yang menembak ke atas rumah kedai orang Cina kerana kononnya mereka telah membaling botol ke arah askar melayu tersebut. Ada yang berkata askar tersebut berpakaian preman.Ramai orang Cina dibunuh dan dicampakkan ke dalam lombong bijih timah di Sungai Klang berhampiran lorong Tiong Nam, Chow Kit. Konon ada rakaman televisyen oleh pemberita dari BBC dan Australia, beberapa pemuda Cina ditangkap, dibariskan di tepi lombong dan dibunuh. Bagaimanapun, sehingga sekarang, tiada bukti yang diedarkan mengenai rakaman ini.

Panggung Odeon

Pemuda-pemuda Cina telah bertindak mengepung Panggung Odeon, di Jalan Tuanku Abdul Rahman, Kuala Lumpur. Beberapa iklan disiarkan dalam bahasa Cina di skrin pawagam menyuruh penonton dari kalangan Cina keluar dari panggung. Penonton Melayu di panggung tersebut langsung tidak tahu membaca tulisan bahasa cina. Kesan daripada itu, pemuda-pemuda cina tersebut telah menyerbu masuk ke dalam panggung dan menyerang dan menyembelih penonton yang ada. Hampir semua penonton di dalam panggung tersebut mati di dalam keadaan yang sangat mengerikan. Ini termasuklah dua orang Askar Melayu yang tinggal di Sungai Ramal, Kajang. Manakala di pasar pula askar melayu telah menembak orang cina yang melanggar perintah berkurung dengan kereta perisai mereka. Di lebuh raya persekutuan pula, penduduk melayu Kampung Kerinchi telah membuang pasu di atas lebuhraya tersebut dan mengakibatkan kesesakan lalulintas dan kemalangan. Pemilik kereta berbangsa cina ditetak dan dibunuh. Seluruh keluarga peniaga cina yang menjual bunga berdekatan habis dibunuh. Di lapangan terbang Sungai Besi waktu itu yang merupakan lapangan terbang antarabangsa, askar melayu telah menembak orang Cina yang baru balik dari luar negeri dengan tanggapan bahawa mereka melanggar perintah berkurung.Seorang polis bernama Rahim yang tinggal di Kuala Lumpur yang turut menonton wayang di Odeon terkena tetakan di kepala dan berpura-pura mati. Beliau masih hidup hingga sekarang. Sementara Mohd Radzi mengalami pengalaman yang sama di Pawagam Federal, Jalan Chow kit, Kuala Lumpur ketika menonton filem The Came To Rob Las Vegas arahan antonio Isasi Isasmendi. Akibat daripada tindakan sebegini, orang-orang Melayu mulai bertindak balas, dan dikatakan kepala orang Cina yang dibunuh diletakkan di atas pagar.

Abdul Rafai Alias bersama rakan-rakannya dari Semenyih yang datang ke Kuala Lumpur turut terperangkap dan terkejut dengan rusuhan kaum yang tidak disangka-sangka pada 13 Mei itu. Beliau turut melangkah-langkah mayat mereka yang telah terbunuh di atas jalan.

Khabar angin mengatakan Tentera Sabil dari Sungai Manik hendak datang ke Kampung Baru tetapi tersekat. Begitu juga dengan Tentera Selempang Merah dari Muar dan Batu Pahat tersekat dan disekat oleh polis di Balai Polis Kajang dan Cheras.

Ada 4 kiyai di sekitar Kampung Baru mengedarkan air jampi dan tangkal penebat, iaitu ilmu kebal dengan harga yang agak mahal. Sesiapa yang memakainya menjadi kebal dan boleh terbang. Apa yang pasti, Askar Melayu juga telah menyelamatkan orang Melayu di Kampung Baru ketika itu. Mungkin juga ramai yang pernah mendengar kisah parang terbang yang terbang di Kampung Cheras Baru dan penggal kepala orang Cina.

Namun rusuhan kaum tidak terjadi di Kelantan, Terengganu dan Pahang. Di Perak, Kedah, Pulau Pinang serta Perlis tiada sebarang pergaduhan. Negeri Johor dan Negeri Sembilan juga tidak terjadi apa-apa kerana telah diberi amaran oleh PKM. Cuma ada sedikit kekecohan di Melaka. Di Betong ada tembakan dilepaskan oleh PKM dan mereka memberi amaran jika askar melayu menembak orang cina, mereka akan memberi senjata api kepada orang cina.

Ada yang menyifatkan pergaduhan ini sebenarnya adalah pergaduhan "politik" Datuk Harun dengan sokongan Tun Razak yang tidak berpuas hati dengan Tunku Abdul Rahman bukannya perkauman kerana pemimpin cina Parti Perikatan seperti, Tan Siew Sin, Ong Yoke Lin telah "lari" bersama dengan Tunku Abdul Rahman ke Cameron Highlands. Sebelum peristiwa itu masyarakat Melayu dan Cina boleh hidup dalam keadaan yang harmoni. Seperti dinyatakan pergaduhan tidak belaku di negeri seperti Kelantan, Pahang dan Kedah. Jika ia merupakan isu perkauman, pastinya pada hari itu orang cina dan melayu akan berbunuhan sesama sendiri di negeri tersebut seperti di selatan thai.

Persepsi

Kalangan orang melayu mempunyai pandangan yang negatif terhadap kaum cina yang dilihat sebagai tidak mengenang budi dengan taraf kerakyatan yang diberikan pada mereka pasca kemerdekaan. Persepsi negatif masyarat Melayu terhadap kaum Cina juga berlaku kerana orang Cina merupakan majoriti menganggotai pasukan Bintang Tiga yang ingin menjadikan negara ini sebagai negara komunis berpaksikan negara komunis China.Pada tahun 2007, satu buku — May 13: Declassified Documents on the Malaysian Riots of 1969 yang ditulis oleh akademik, bekas ahli Democratic Action Party, dan bekas ahli parlimen Kua Kia Soong — telah diterbit oleh Suaram. Berdasarkan dokumen yang baru 'declassified' di pejabat maklumat awam London, buku tersebut mengatakan bahawa rusuhan tersebut bukannya disebabkan parti pembangkang sepertimana cerita rasmi yang diberikan, tetapi rusuhan tersebut dimulakan oleh "ascendent state capitalist class" di UMNO sebagai 'coup d'etat' untuk menumbangkan Tunku Abdul Rahman.[4]

Angka korban

Angka rasmi menunjukkan 196 mati, 439 cedera, 39 hilang dan 9,143 ditahan. 211 kenderaan musnah. Tapi ramai telah menganggar ramai lagi dibunuh. Sebuah thesis PhD. daripada Universiti California, Berkeley menganggar seramai 20,000 orang hilang nyawa dalam peristiwa 13 Mei. [5]Statistik tidak rasmi jumlah kematian:

- Melayu : 86 orang

- Cina : 342 orang

- Lain-lain : 3 orang

Lokasi Tunku Abdul Rahman semasa peristiwa 13 Mei

Ketika itu (13 Mei 1969), Tunku Abdul Rahman baru pulang dari Alor Star meraikan kemenangan beliau di sana.6.45 petang Encik Mansor selaku Ketua Polis Trafik Kuala Lumpur memaklumkan kejadian pembunuhan kepada Tunku Abdul Rahman. Darurat diisytiharkan pada jam 7.00 malam 13 Mei 1969. Ada khabar angin mengatakan Tunku sedang bermain mahjung dan ada khabar menyatakan Tunku sedang menikmati hidangan arak. Dalam tulisannya, Tunku menafikan hal tersebut. Pada malam peristiwa itu di televisyen, Tunku berkata "Marilah kita tentukan sekarang bahawa sama ada kita hidup atau mati".

Mageran

Negara diisytiharkan darurat pada malam 16 Mei 1969. Dengan pengistiharan ini, Perlembagaan Persekutuan telah digantung. Negara diperintah secara terus oleh Yang DiPertuan Agong dibawah undang-undang tentera. Dalam pada itu, Mageran telah dibentuk. Tunku Abdul Rahman telah menarik diri dari mengetuai majlis tersebut. Tempat beliau telah digantikan oleh Timbalan Perdana Menteri Tun Abdul Razak. Berikutan itu, Parlimen juga digantung.Sesetangah orang melayu mempersalahkan Tunku Abdul Rahman kerana gagal membendung ancaman rusuhan perkauman tersebut. Di antara tokoh yang lantang menghentam Tunku ialah Tun Dr Mahathir menerusi buku "Dilema Melayu" ("Malay Dilemma"). Buku tersebut pernah diharamkan oleh Tunku.

Sepanjang tempoh darurat, Mageran telah melakukan pelbagai tindakan untuk mencari punca dan penyelesaian agar trajedi tersebut tidak berulang. Diantara tindakan yang diambil ialah membentuk satu Rukun Negara bagi meningkatkan kefahaman rakyat pada perlembagaan negara. Turut dilakukan ialah melancarkan Dasar Ekonomi Baru untuk menghapuskan pengenalan kaum dengan satu aktiviti ekonomi dan membasmi kemiskinan tegar dan membentuk Barisan Nasional yang bersifat sebagai sebuah kerajaan perpaduan. Hampir kesemua parti yang bertanding pada 1969 telah menyertai BN kecuali DAP.

Sunday May 11, 2008

May 13, 1969: Truth and reconciliation

By MARTIN VENGADESAN

Closure: ‘A bringing to an end; a conclusion... A feeling of finality or resolution, especially after a traumatic experience,’ (Answers.com). Well, May 13, 1969, was truly a traumatic experience for Malaysia. Yet 39 years later, there is still no proper closure. Instead, the incident has haunted the nation these past four decades. Just the mention of ‘May 13’ invokes shudders and nervous glances. It is our national ‘code’ for violent racial meltdown, especially among the older generation. Isn’t it time to finally break the code?

WHEN news of the March 8 general election results broke, Opposition supporters were understandably jubilant at what was their best showing in the nation’s 51-year history. Yet, the sentiment on the ground was very much one of restraint. Supporters were urged not to go out and celebrate, but rather to maintain a low profile.

The reason for such caution: The racial riots of May 13, 1969, of course.

Kampung Baru in Kuala Lumpur was the gathering point for a counter victory march on May 13, 1969.

Kampung Baru in Kuala Lumpur was the gathering point for a counter victory march on May 13, 1969. According to a Time magazine report on May 23, 1969, ”Malaysia’s proud experiment in constructing a multiracial society exploded in the streets of Kuala Lumpur last week. Malay mobs, wearing white headbands signifying an alliance with death, and brandishing swords and daggers, surged into Chinese areas in the capital, burning, looting and killing. In retaliation, Chinese, sometimes aided by Indians, armed themselves with pistols and shotguns and struck at Malay kampongs. Huge pillars of smoke rose skyward as houses, shops and autos burned.”

That was an outsider view of what happened. Yet, almost four decades later, that is the same graphic image associated with May 13 – violence, mayhem, killing – which haunts Malaysians.

As a nation we have not moved or completely healed from the incident simply because we have been afraid. As PKR information chief Tian Chua opined in an interview with StarMag: “In Malaysia, we grow up and live in a culture of fear in the shadow of May 13. That fear has been built into our political system and has remained a part of our psychology.”

That fear is, in part, rooted in ignorance: no one has been able to come up with a full and authoritative account of what happened.

Prof Datuk Dr Shamsul Amri Baharuddin

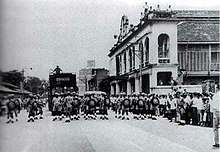

Prof Datuk Dr Shamsul Amri Baharuddin Umno Youth members then gathered at Selangor Menteri Besar Datuk Harun Idris’s residence in Kampung Baru in KL on May 13 for their own counter victory celebration since the Alliance had maintained its majority in Parliament, albeit a reduced one, and had retained Selangor with the support of the single independent assemblyman.

That led to outbreaks of violence in parts of Kuala Lumpur that continued over the following days. Houses, shops, vehicles were torched, people killed and injured. Official figures put the death toll at less than 200 but many commentators put the figures at between 800 and 1,000.

On the day the riots broke out, Star Deputy Op-Ed Editor Johan Fernandez , then 21, was watching a movie in the heart of KL.

“Suddenly the screen went red and the words ‘Emergency Declared’ in large black letters were flashed. There was a mad rush to lock the cinema gates just as an armed gang tried to break in.

At first I joined many who were hiding in the toilets but I didn’t want to die there so I walked out again just as the gang broke through, ready to kill. But I heard them say among themselves that they weren’t targeting my race, so I plucked up my courage and walked out of the hall. I know that people were killed after I left.

“I took refuge in a nearby police station for about five or six days until the killings stopped.”

Many Malaysians living in KL at that time have similar tales to tell or know of someone who suffered losses.

After so many years, the question that is often murmured or thought about is: Can another May 13 recur? Certainly it was considered a possibility after the March 8 general election as the results bore an uncanny resemblance to that of 1969.

Prof Emeritus Datuk Dr Khoo Kay Kim says that the circumstances surrounding May 13 were different.

“I believe that this time around there was a greater determination to preserve the peace. I think the security forces were a little confused in 1969, which is why (then Home Minister) Tun Dr Ismail had to bring in the Sarawak rangers.”

Dr Kua Kia Soong

Dr Kua Kia Soong “A focal point of May 13 was communal divisions. Even though the Alliance had lost Kelantan to PAS, many contests were largely pitched as Malay versus non-Malay. It was the non-Malay vote that swung very sharply to the then Opposition parties of Gerakan, DAP and PPP.

“In the case of March 8, the support for the Pakatan Rakyat parties came from all three major races so the situation therefore was far less explosive.”

The historical background

Many tumultuous events happened in the years leading to May 13. Malaya gained independence in 1957 against the backdrop of a guerrilla war conducted by the Communist Party of Malaya (the Emergency which lasted from 1948-1960).

In 1963, Singapore, Sabah and Sarawak joined Malaya to form Malaysia, against the objections of the Filipino and Indonesian governments of the day. Indonesian President Sukarno was particularly incensed and carried out underground military action during this period (known as the Konfrontasi).

Meanwhile in Brunei, an election was held but its results nullified when the leftist Parti Rakyat Brunei (which advocated union with Indonesia) swept all the seats, resulting in the brief Brunei Revolt.

In 1965 Singapore seceded from Malaysia, thanks in part to two separate rounds of race riots in 1964 (on July 21 and Sept 3) during which nearly 50 people died in Sino-Malay clashes.

Prof Emeritus Datuk Dr Khoo Kay Kim

Prof Emeritus Datuk Dr Khoo Kay Kim The 1969 general elections were therefore conducted under highly emotional charged circumstances.

The theories

In May 13 Before And After, a book penned by Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman within months of the riots, he laid blame largely on communist agitators as well as their leftist sympathisers within the Labour Party of Malaya. LPM chose to boycott the 1969 general election but nonetheless showed off their strength at the funeral march of a member, Lim Soon Seng (who was killed in a clash with police), held in Kepong on May 9.

Tunku also accused supporters of two opposition parties fighting their first general election – Gerakan (a multi-racial party which included former Labour Party leaders Tan Sri Dr Tan Chee Koon and Dr V. David) and the DAP (a splinter party of Singapore’s ruling People’s Action Party) – with carrying out provocative celebrations in Malay areas like Kampung Baru.

Other factors cited by Tunku in his book are the power struggle within Umno itself and the emergence of Malay “ultras”.

Prof Datuk Dr Shamsul Amri Baharuddin, founding director of Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia’s Institute of Ethnic Studies, says the most common misconception about May 13 is that it was caused by a single factor.

“In reality, it was the result of multiple factors. Like the movie Vantage Point which presents eight viewpoints from eight persons on one event (the attempt to assassinate a US President), there can be many vantage points to May 13: official, personal and even conspiratorial ones,” he adds.

Dr Kua Kia Soong, author of May 13: Declassified Documents on the Malaysian Riots of 1969 released last year, is of the view that the May 13 riots were not a spontaneous uprising but an orchestrated coup against Tunku by disaffected members of his own party.

Former Inspector-General of police Tun Hanif Omar, in his Sunday Star column on June 3, 2007, rejected this claim.

He pointed out that the National Operations Council (NOC) Report, The May 13, 1969 Incidents, gave other reasons why and how the outbreak started and its consequences.

“Is the NOC Report accurate without touching on the plot to topple Tunku? To me it is. The unhappiness that some Umno members had with Tunku by 1969 was real but it did not feature as a cause of the May 13 incident.

“The incident, however, sharpened the unhappiness of the Malays with Tunku and fuelled the movement to replace him with his deputy, Tun Abdul Razak.

“As the coordinator of the Special Branch investigations into the incident, and having read all the statements from eye-witnesses which formed the basis of the NOC Report, I am convinced of its accuracy,” wrote Hanif.

Still, what Ahmad Mustapha Hassan ,who was an Umno Youth exco committee member at the time, saw first-hand seems to lend some credence to the Tunku conspiracy theory.

He explains: “I was part of the Umno Youth committee that held a meeting on the morning of May 13 and our plan was clear. We would hold a counter victory celebration, to remind people that even though we had a smaller majority we were still victorious.

“However, when we assembled at the Selangor Mentri Besar’s house shocking incidents happened. We were handed headbands and weapons were produced. It was definite that there were some elements in Umno who were opposed to Tunku’s leadership and who had come with an ulterior motive and planned something more sinister.”

In his book, The Unmaking of Malaysia, Ahmad describes his grief and horror at the events that unfolded: “I witnessed a killing of an innocent coffee shop boy. ... We were unaware and unprepared for such a situation ... A crazy mob had taken over ... and I and fellow Umno Youth (members) were helpless.”

Ahmad, who went on to serve as press secretary to Prime Ministers Tun Abdul Razak and Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad, believes the attacks “appeared to be planned by some group because hidden weapons and headbands were distributed” but maintains he does not know who was responsible.

It is Dr Kua’s contention that unless “the truth is out”, there can be no real national unity. But Hanif countered that what happened in 1969 “was too ‘ancient’ an animosity to be allowed to hold national unity to ransom.”

In an interview last week, Dr Kua argues that “May 13 is part of our history and is consistently trotted out by politicians who want to play the racial card, to show us what will happen if the privileges of the ruling class are threatened. We need to have a process of truth and reconciliation. This is what happened in South Africa after apartheid; it doesn’t bring back the dead, but it lets the healing process begin.

“At the moment the blame is put largely on the back of the Opposition, but questions must be asked about the role of the military, the police and certain ruling party officials who represented the emerging capitalist class. We don’t need to trot out the gory details which will inflame passions, but the truth must not be covered up.”

DAP veteran leader Lim Kit Siang, who was detained under the Internal Security Act for more than a year after the riots, agrees, adding that 40 years is not too late to discuss what happened.

“We should stop sweeping it under the carpet. May 13 is a ghost that must be exorcised. As long as it remains a hidden, censored part of history then it hinders our maturing as a people and a nation, and will continue to haunt us.”

This desire for closure is shared by others.

In a letter to The Star, (Bury ghost of May 13 once and for all, March 27) Lt Kol (R) Mohd Idris Hassan took to task a “seasoned politician” for appearing on TV and ”saying that if the Opposition parties continue to fan communal sentiments, another May 13 will happen, adding with a raised index finger ‘Dan jangan salahkan kami’ (Then don’t blame us).”

Mohd Idris went on to say “please spare us the threat of another dreadful May 13” and that “After 39 years, it is time to bury deep the ghost of May 13 once for all, so that it never raises its ugly head again.”

He added: “For one, it is a well-flogged threat used by some politicians for their own agenda, and two, it does not work any more. All it does is that it raises painful memories of the black chapter in our history of our otherwise harmonious relations between all races.

“On that fateful day, I was a young officer serving in the army. I witnessed first-hand the carnage as it unfolded. People were attacked because they were of the wrong race, at the wrong place at the wrong time. Everyone suffered.”

Responding to Mohd Idris’ letter, another reader, Daniel K.C. Lim, wrote that “rather than trying to decipher the truth from the official version, if one exists, or from listening to unofficial or underground versions, or simply putting every rumour on hold until living memories fade away and are replaced by mere myths and legends, why not have the events of May 13, 1969, properly and definitively recorded and reviewed?

“Reconciliation must start first with the truth; only then will we be able to lay matters well to rest once and for all.”

Teoh Feh Leong, a 55-year-old engineer, feels that closure can only come through acknowledgement and forgiveness.

“We don’t know anything about what happened because the Government has closed this entire chapter of our history. The incident happened too far back for us to hate or incite anger anymore. But we need to know what happened factually, accurately, once and for all.

“Our young Malaysians have no idea what’s May 13 while the older people remain bitter. Unless we acknowledge and confess to what happened, the spirit of May 13 will continue to be present each time the Malays feel threatened or when the Chinese feel cheated or outraged. It will never end.”

Among the younger generation, May 13 may hold little fear for them but there is a certain curiosity about it.

Abby Wong, 38, merchandising manager for a KL leading bookstore believes that was what fuelled the good sales of Dr Kua’s book.

“It sold like hot cakes when it came out last year. Most of the buyers were working adults in their 30s. When I asked them how they knew about it since there was little publicity in the press, they told me they found out about it on the Internet and were curious to know more.

“I remember one buyer described the book as ‘Valuable history at a cheap price’ as it was sold at only RM20,” says Wong.

Student Chak Tze Chin, 23, says she heard stories of it from her grandmother.

“She still thinks there can be another May 13 incident so during the last general election, she advised me to stay home. To me, it’s important to understand past events so that we can work together better in the future.”

To Diana Afandi, May 13 is often used to remind the people of Malaysia not to stir up racial tensions. “But now, it is used so widely for political parties and leaders to pursue their objectives. I remember being nervous when I heard the stories from my parents and I am still worried now,” said the 21-year-old student.

Other flashpoints

Perhaps what should be made known is that May 13 was not the only major racial clash in the country’s history.

Dr Khoo explains: “The first racial riots were in August-September 1945 and were caused by the Communist Party of Malaya going around punishing Chinese and Indian collaborators after the Japanese Occupation ended. But when they punished the Malays, especially the Banjaris in the Batu Pahat area, they fought back. And this spread to other Banjari areas like Batu Kikir in Negri Sembilan and Sungai Manik in Perak.”

Prof Shamsul agrees: “May 13 has been given special attention in our media, history books and realpolitik, but the Sino-Malay ethnic riots in 1945 were bigger and bloodier. They were more widespread and continued for a longer period (for two weeks with a toll estimated at more than 2,000 lives).

“Why is this conflict never mentioned every time we talk about racial riots in Malaysia? It reminds me of what French historian Ernest Renan once said: ‘History is about remembering and forgetting.’

“It is historical, therapeutic and awareness-raising to talk and analyse these conflicts (between 1945 and 1969) in a rational and reasoned manner, and not use it as a threat to incite racial hatred or fulfil an ethnicised political agenda.”

Observes Dr Khoo: “People try not to talk about May 13 because they don’t know how to handle it. You cannot start by blaming one side or another. The procession through Kampung Baru was certainly unfortunate, but it did not justify such a wave of killings.

“After 1969 we became vulnerable. Each race is told that it is somebody else’s fault. We expect our leaders to play a part in defusing tensions, but instead there are many who thrive on constantly fuelling the fears of the people.”

Moving on

Still there are positive signs of a maturing society, such as how the March 8 general election results were accepted without any violence.

Admits Dr Kua, “The recent elections just put paid to my theory that such riots might recur if the government lost its two-thirds majority.”

Dr Khoo concludes: May 13 is not just a story. It tells about our society and its relationships. We must reach a stage where we understand each other’s fears, where cultural diversity is accepted and not be the cause of conflict.

“Everybody should also realise, especially our politicians, that you can never solve sensitive issues by confrontation.

“People should be reminded that Barisan Nasional was formed after May 13 after the Alliance Party (of Umno, MCA and MIC) was broadened to include former opposition parties, the reason being that the huge coalition would help reduce inflammatory politicking.

“Ethnic champions should always be disapproved of in a multi-ethnic society.”

Timeline 1969-1973

1969Late April – campaigning period sees clashes in Penang with an Umno worker killed.

May 9 – Funeral of Labour Party member in Kepong turns into show of strength by leftists.

May 10 – General Election is held resulting in Alliance Party losing its two-thirds majority, as well as the state legistatures of Kelantan and Penang. Perak and Selangor state assemblies are hung.

May 11&12 – Supporters of Gerakan and DAP go on victory processions, during which racial taunts are made.

May 13 – Umno organises counter procession beginning at the residence of Selangor Menteri Besar Datuk Harun Idris. Racial killings begin. Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman addresses the nation. Curfew imposed in Selangor and Kuala Lumpur.

May 14 – State of Emergency declared as retaliatory killings continue. Officially 196 people are killed during this period, but unofficial estimates put the figure closer to 800-1,000.

May 16 – National Operations Council headed by Deputy Prime Minister Tun Abdul Razak is appointed by Yang-Di-Pertuan Agong to carry out executive duties in place of suspended Parliament. Tun Dr Ismail is appointed Minister of Internal Security.

June 28 – Five people are killed in Malay-Indian clashes in KL.

1970 June/July – Elections in Sabah and Sarawak are held.

1971 Feb 21 –Parliament reconvened and National Operations Council dissolved. New Economic Policy launched to ensure a more equitable distribution of wealth among the races.

1972

January – Gerakan and PPP agree to work with Alliance in running Penang and Perak state governments respectively.

1973 January – PAS joins the Alliance, leading to formalisation of new coalition as Barisan Nasional.

- Source: May 13 Before And After; May 13: Declassified Documents on the Malaysian Riots of 1969; Wikipedia

May 13 incident

The May 13 Incident is a term for the Sino-Malay sectarian violences in Kuala Lumpur (then part of the state of Selangor), Malaysia, which began on May 13, 1969. The riots led to a declaration of a state of national emergency and suspension of Parliament by the Malaysian government, while the National Operations Council (NOC or Majlis Gerakan Negara, MAGERAN) was established to temporarily govern the country between 1969 and 1971.

Officially, 196 people were killed between May 13 and July 31 as a result of the riots, although journalists and other observers have stated much higher figures. Other reports at the time suggest over 2,000[citation needed] were killed by rioters, police and Malaysian Army rangers, mainly in Kuala Lumpur. Many of the dead were quickly buried in unmarked graves in the Kuala Lumpur General Hospital grounds by soldiers of Malaysian Engineers.

The government cited the riots as the main cause of its more aggressive affirmative action policies, such as the New Economic Policy (NEP), after 1969.

Formation of Malaysia

On its formation in 1963, Malaysia, a federation incorporating Malaya (Peninsular Malaysia), Singapore, North Borneo (Sabah) and Sarawak, suffered from a sharp division of wealth between the Chinese, who were perceived to control a large portion of the Malaysian economy, and the Malays, who were perceived to be more poor and rural.

The 1964 Race Riots in Singapore contributed to the expulsion of that state from Malaysia on 9 August 1965, and racial tension continued to simmer, with many Malays dissatisfied by their newly independent government's perceived willingness to placate the Chinese at their expense.

Ketuanan Melayu

Politics in Malaysia at this time were mainly Malay-based, with an emphasis on special privileges for the Malays — other indigenous Malaysians, grouped together collectively with the Malays under the title of "bumiputra" would not be granted a similar standing until after the riots. There had been a recent outburst of Malay passion for ketuanan Melayu — a Malay term for Malay supremacy or Malay dominance — after the National Language Act of 1967, which in the opinion of some Malays, had not gone far enough in the act of enshrining Malay as the national language. Heated arguments about the nature of Malay privileges, with the mostly Chinese opposition mounting a "Malaysian Malaysia" campaign had contributed to the separation of Singapore on 9 August 1965, and inflamed passions on both sides.1969 general election

Main article: Malaysian general election, 1969

Run-up to polling day

The causes of the rioting can be analysed to have the same root as the 1964 riots in Singapore, the event rooted from sentiments before the campaigning was bitterly fought among various political parties prior to polling day on 10 May 1969, and party leaders stoked racial and religious sentiments in order to win support. The Pan Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS) accused the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) of selling the rights of the Malays to the Chinese, while the Democratic Action Party (DAP) accused the Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA) of giving in to UMNO. The DAP promoted the concept of a "Malaysian Malaysia", which would deprive the Malays of their special rights under the Constitution of Malaysia. Both the DAP and Singapore's People's Action Party (PAP) objected to Malay as the national language and proposed multi-lingualism instead.[1] Senior Alliance politicians, including Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman, accused Singapore-based People's Action Party of involvement in the campaign, as it had done during the 1964 general election campaign (at the time when Singapore was part of the Malaysian federation between 1963 and 1965).The run-up to the election was also marred by two deaths: that of an UMNO election agent, who was killed by a group of armed Chinese youths in Penang and that of a member of the Labour Party of Malaya (LPM), who was killed in Kepong, Selangor.[1] There was a contrast in the handling of these two deaths. The UMNO worker was buried without publicity, but the LPM casualty was honoured at a parade on May 9 when some 3000 LPM members marched from Kuala Lumpur to Kepong, violating regulations and trying to provoke incidents with the police. The participants sang Communist songs, waved red flags, and called upon the people to boycott the general election.

Election results

Amidst tensions among the Malay and Chinese population, the general election was held on 10 May 1969. Election day itself passed without any incidents, and the results showed that the Alliance had gained a majority in Parliament at the national level, albeit a reduced one, and in Selangor it had gained the majority by cooperating with the sole independent candidate. The Opposition had tied with the Alliance for control of the Selangor state legislature, a large setback in the polls for the Alliance. On the night of 11th and 12th May, the Opposition celebrated their victory. In particular, a large Gerakan procession welcomed the left-wing Gerakan leader V. David.[2]On 12 May, thousands of Chinese marched through Kuala Lumpur, parading through predominantly Malay areas, hurling insults which led to the incident.[1] The largely Chinese opposition Democratic Action Party and Gerakan gained in the elections, and secured a police permit for a victory parade through a fixed route in Kuala Lumpur. However, the rowdy procession deviated from its route and headed through the Malay district of Kampung Baru, jeering at the inhabitants.[3] Some demonstrators carried brooms, later alleged to symbolise the sweeping out of the Malays from Kuala Lumpur, while others chanted slogans about the "sinking" of the Alliance boat — the coalition's logo.[4] The Gerakan party issued an apology on May 13 for their rally goers' behaviour.

In addition, Malay leaders who were angry about the election results used the press to attack their opponents, contributing to raising public anger and tension among the Malay and Chinese communities.[citation needed] On 13 May, members of UMNO Youth gathered in Kuala Lumpur, at the residence of Selangor Menteri Besar Dato' Harun Haji Idris in Jalan Raja Muda, and demanded that they too should hold a victory celebration. While UMNO announced a counter-procession, which would start from the Harun bin Idris's residence. Tunku Abdul Rahman would later call the retaliatory parade "inevitable, as otherwise the party members would be demoralised after the show of strength by the Opposition and the insults that had been thrown at them."[3]

Rioting

Go to following pages for more accurate information,a speech by Prime Minister TUNKU ABDUL RAHMAN :- http://mt.m2day.org/2008/content/view/12512/84/Shortly before the UMNO procession began, the gathering crowd was reportedly informed that Malays on their way to the procession had been attacked by Chinese in Setapak, several miles to the north.[citation needed] Meanwhile, in the Kuala Lumpur area, a Malay army officer was murdered by Chinese radicals as he and his spouse were coming out from a movie theater in the predominantly Chinese area of Bukit Bintang[citation needed]. A group of Malay protestors swiftly wreaked revenge by killing two innocent passing Chinese motorcyclists, and the riot began.

The riot ignited the capital Kuala Lumpur and the surrounding area of Selangor — according to Time, spreading throughout the city in 45 minutes.[5] Many people in Kuala Lumpur were caught in the racial violence—dozens were injured and some killed, houses and cars were burnt and wrecked, but except for minor disturbances in Malacca, Perak, Penang and Singapore, where the populations of Chinese people were similarly larger, the rest of the country remained calm. Although violence did not occur in the rural areas, Time found that ethnic conflict had manifested itself in subtler forms, with Chinese businessmen refusing to make loans available for Malay farmers, or to transport agricultural produce from Malay farmers and fishermen.[6]

Incidents of violence continued to occur in the weeks after May 13, with the targets now being not only Malay or Chinese but also Indian. It is argued that this showed that "the struggle has become more clearly than ever the Malay extremists' fight for total hegemony."[7]

According to police figures, 196 people died[8] and 149 were wounded. 753 cases of arson were logged and 211 vehicles were destroyed or severely damaged. An estimated 6,000 Kuala Lumpur residents — 90% of them Chinese[verification needed] — were made homeless.[8] Various other casualty figures have been given, with one thesis from a UC Berkeley academic, as well as Time, putting the total dead at ten times the government figure.[7][9]

Declaration of emergency

The government ordered an immediate curfew throughout the state of Selangor. Security forces comprising some 2000 Royal Malay Regiment soldiers and 3600 police officers were deployed and took control of the situation. Over 300 Chinese families were moved to refugee centres at the Merdeka Stadium and Tiong Nam Settlement.On May 14 and May 16, a state of emergency and accompanying curfew were declared throughout the country, but the curfew was relaxed in most parts of the country for two hours on May 18 and not enforced even in Kuala Lumpur within a week.[citation needed]. On May 16 the National Operations Council (NOC) was established by proclamation of the Yang di-Pertuan Agong (King of Malaysia) Sultan Ismail Nasiruddin Shah, headed by Tun Abdul Razak. With Parliament suspended, the NOC became the supreme decision-making body for the next 18 months. State and District Operations Councils took over state and local governments.

The NOC implemented security measures to restore law and order in the country, including the establishment of an unarmed Vigilante Corps, a territorial army, and police force battalions. The restoration of order in the country was gradually achieved. Curfews continued in most parts of the country, but were gradually scaled back. Peace was restored in the affected areas within two months. In February 1971 parliamentary rule was re-established.

In a report from the NOC, the riots was attributed in part to both the Malayan Communist Party and secret societies:

| “ | The eruption of violence on May 13 was the result of an interplay of forces... These include a generation gap and differences in interpretation of the constitutional structure by the different races in the country...; the incitement, intemperate statements and provocative behaviours of certain racialist party members and supporters during the recent General Election; the part played by the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) and secret societies in inciting racial feelings and suspicion; and the anxious, and later desperate, mood of the Malays with a background of Sino-Malay distrust, and recently, just after the General Elections, as a result of racial insults and threat to their future survival in their own country' | ” |

— Extract from The May 13 Tragedy, a report by the National Operations Council, October 1969.[1] |

Conspiracy theories

Immediately following the riot, conspiracy theories about the origin of the riots began swirling. Many Chinese blamed the government, claiming it had intentionally planned the attacks beforehand. To bolster their claims, they cited the fact that the potentially dangerous UMNO rally was allowed to go on, even though the city was on edge after two days of opposition rallies. Although UMNO leaders said none of the armed men bused in to the rally belonged to UMNO, the Chinese countered this by arguing that the violence had not spread from Harun Idris' home, but had risen simultaneously in several different areas. The armed Malays were later taken away in army lorries, but according to witnesses, appeared to be "happily jumping into the lorries as the names of various villages were called out by army personnel".[10]Despite the imposition of a curfew, the Malay soldiers who were allowed to remain on the streets reportedly burned several more Chinese homes. The government denied it was associated with these soldiers and said their actions were not condoned.[10] However, Western observers such as Time suggested that "Whether or not the Malay-controlled police force and emergency government have actually stirred up some of the house-burning, spear-carrying mobs, they seem unwilling to clamp down on them."[7]

In 2007, a book — May 13: Declassified Documents on the Malaysian Riots of 1969 by academic, former Democratic Action Party member and former Member of Parliament Kua Kia Soong — was published by Suaram. Based on newly declassified documents at the Public Records Office in London, the book alleged that contrary to the official account that had blamed the violence on opposition parties, the riot had been intentionally started by the "ascendent state capitalist class" in UMNO as a coup d'etat to topple Tunku Abdul Rahman.[11][12]

Repercussions

Immediate effects

Immediately after the riot, the government assumed emergency powers and suspended Parliament, which would reconvene again only in 1971. It also suspended the press and established a National Operations Council. The NOC's report on the riots stated, "The Malays who already felt excluded in the country's economic life, now began to feel a threat to their place in the public services," and implied this was a cause of the violence.[3]Western observers such as Time attributed the racial enmities to a political and economic system, which primarily benefited the upper classes:

| “ | The Chinese and Indians resented Malay-backed plans favoring the majority, including one to make Malay the official school and government language. The poorer, more rural Malays became jealous of Chinese and Indian prosperity. Perhaps the Alliance's greatest failing was that it served to benefit primarily those at the top. ... For a Chinese or Indian who was not well-off, or for a Malay who was not well-connected, there was little largesse in the system. Even for those who were favored, hard feelings persisted. One towkay recently told a Malay official: "If it weren't for the Chinese, you Malays would be sitting on the floor without tables and chairs." Replied the official: "If I knew I could get every damned Chinaman out of the country, I would willingly go back to sitting on the floor."[13] | ” |

Tunku Abdul Rahman resigned as Prime Minister in the ensuing UMNO power struggle, the new perceived 'Malay-ultra' dominated government swiftly moved to placate Malays with the Malaysian New Economic Policy (NEP), enshrining affirmative action policies for the bumiputra (Malays and other indigenous Malaysians). Many of Malaysia's draconian press laws, originally targeting racial incitement, also date from this period. The Constitution (Amendment) Act 1971 named Articles 152, 153, and 181, and also Part III of the Constitution as specially protected, permitting Parliament to pass legislation that would limit dissent with regard to these provisions pertaining to the social contract. (The social contract is essentially a quid pro quo agreement between the Malay and non-Malay citizens of Malaysia; in return for granting the non-Malays citizenship at independence, symbols of Malay authority such as the Malay monarchy became national symbols, and the Malays were granted special economic privileges.) With this new power, Parliament then amended the Sedition Act accordingly. The new restrictions also applied to Members of Parliament, overruling Parliamentary immunity; at the same time, Article 159, which governs Constitutional amendments, was amended to entrench the "sensitive" Constitutional provisions; in addition to the consent of Parliament, any changes to the "sensitive" portions of the Constitution would now have to pass the Conference of Rulers, a body comprising the monarchs of the Malay states. At the same time, the Internal Security Act, which permits detention without trial, was also amended to stress "intercommunal harmony".[14]

Despite the opposition of the DAP and PPP, the Alliance government passed the amendments, having maintained the necessary two-thirds Parliamentary majority.[14] In Britain, the laws were condemned, with The Times of London stating they would "preserve as immutable the feudal system dominating Malay society" by "giving this archaic body of petty constitutional monarchs incredible blocking power"; the move was cast as hypocritical, given that Deputy Prime Minister Tun Abdul Razak had spoken of "the full realisation that important matters must no longer be swept under the carpet..."[15]

The Rukunegara, the de facto Malaysian pledge of allegiance, was another reaction to the riot. The pledge was introduced on August 31, 1970 as a way to foster unity among Malaysians.

Legacy

The state of emergency that was declared shortly after the incident has never been lifted, an action that has been cited by academic lawyers as a reason for diminished civil rights in the country due to the legislative powers granted to the executive during a state of emergency.[16]Many political analysts attributed the Malay "crutch mentality" syndrome to have arisen from May 13, and a direct result of the affirmative NEP programme. This had resulted to abnormally large proportion of younger generation of Malays not being able to compete not only internationally but also nationally.

Aftermath

The National Operations Council (NOC) or Majlis Gerakan Negara (MAGERAN) was an emergency administrative body which attempted to restore law and order in Malaysia after the May 13 Incident in 1969, when racial rioting broke out in the federal capital of Kuala Lumpur. From 1969 to 1971, the NOC governed the country in lieu of the elected government. In 1971, the NOC was ended with the restoration of Parliament.The May 13 Incident also led to affirmative action policies, such as the New Economic Policy (NEP), after 1969 and the creation of Kuala Lumpur as a Federal Territory out of Selangor state in 1974, five years later.

Political references

Malaysian politicians have often cited the May 13 incident when warning of the potential consequences of racial rhetoric, or as a bogeyman to blanket off discussion on any issues that challenge the status quo. In the 1990 general election and 1999 general election, May 13 was cited in Barisan Nasional campaign advertisements and in speeches by government politicians. Such usage of the incident in political discourse has been criticised; the Tunku stated: "For the PM (Dr Mahathir Mohamad) to repeat the story of the May 13 as a warning of what would have happened if the government had not taken appropriate action is like telling ghost stories to our children to prevent them from being naughty… The tale should not be repeated because it shows us to be politically immature…"[citation needed]In 2004, during the UMNO general assembly Badruddin Amiruldin , the current deputy permanent chairman, waved a book on May 13 during his speech and stated "No other race has the right to question our privileges, our religion and our leader". He also stated that doing so would be similar to "stirring up a hornet's nest". The next day, Dr Pirdaus Ismail of the UMNO Youth was quoted as saying "Badruddin did not pose the question to all Chinese in the country ... Those who are with us, who hold the same understanding as we do, were not our target. In defending Malay rights, we direct our voice at those who question them." Deputy Internal Security Minister Noh Omar dismissed the remarks as a lesson in history and said that Badruddin was merely reminding the younger generation of the blot on the nation's history.

1969 race riots of Singapore

The 1969 race riots of Singapore were the only riots encountered in post-independence Singapore as a result of the spillover of the May 13 Incident in Malaysia. The seven days of communal riots resulted in the final toll of 4 dead and 80 wounded.[1]

History

The precursor of the 1969 race riots can be traced to the May 13 Incident in Kuala Lumpur and Petaling Jaya in Malaysia. It was triggered by the results of the General Election, that were marked by Sino-Malay riots unprecedented in Malaysian history — 196 people were killed and over 350 injured between May 13 and July 31. The real figures could be much higher than officially revealed. The Malaysian government declared a state of emergency and suspended Parliament until 1971.[1]The disturbances had nothing to do with Singapore but there was an inexorable spillover of the communal violence in Malaysia into Singapore. The 1969 riots occurred not long after the earlier communal riots in 1964. It was said that the 1964 racial disturbances in Singapore contributed towards the eventual separation of Singapore from Malaysia in August 1965. The hysteria that United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) itself generated over its desire to assert Malay dominance (Ketuanan Melayu) in Singapore had its effect in heightening the suspicion between Malay and Chinese in Singapore.[1]

The dissatisfaction of the Malays over their social and economic condition and the fear that the Malays regarded as indigenous (Bumiputra) ownership would be lost, led to the May 13 disturbances.[1]

Rumours and revenge

Rumours began to spread in Singapore about Malay atrocities against the Chinese in Malaysia. People also talked indignantly about the partiality of the Malaysian Armed Forces in dealing with those suspected of involvement in the rioting; Chinese that were caught were severely punished on the spot and these rumours aggravated tension in Singapore.[2] Talk of possible Chinese-Malay clashes in Singapore itself began to spread. There were tales of invulnerable Malays coming to Singapore to help their fellow Malays should they be attacked. These visitors imagined or otherwise, were said to be from Batu Pahat in Malaysia and could make themselves invulnerable to injuries, including bullet wounds.[3]

Reserve Unit Policemen lined the width of Bras Basah Road to reinforce the policemen nearby

These incidents were a prelude to greater violence. Between June 1 and 2, 50 to 60 Chinese attacked houses in Jalan Ubi, Jalan Kayu and its vicinity. They appeared with swords, spears and wooden poles. The first Malay reprisals occurred on June 1. The Black Hawk Malay Secret Society undertook them by setting fires on Chinese-owned shops in Geylang afterwards.[3]

Internal Security Department

The Singapore Immigration, the Singapore Police Force and the Internal Security Department (ISD) made stringent efforts to stop any signs of foreign encroachment. Those who entered were carefully checked, and where necessary were issued warnings. Yet from 31 May to 6 June, four persons were killed and 80 injured.[3]Chinese martial arts gangs had planned a massacre of Malays in the Jalan Ubi area. The ISD was able to prevent this from happening. Roadblocks and police action were adequate in Kampong Glam, where some disturbances had occurred. But it required calling the military including National Servicemen, to set up a cordon round the affected districts in Singapore's north. The Police swept through these districts during a short blitz. The remaining rioters were rounded up on June 6 that finally restored public order to the affected communities.[3]

[edit] Aftermath

After 1971, when all had settled down, the Malaysian government was able to follow an affirmative action policy marked particularly by the New Economic Policy (NEP) favouring the Malays. To this day, there is still an unease about the potential of violence as the power struggles between groups continue.[4]The recent history of what happens in mainland Malaysia shows that it can have an effect in Singapore as both have common cultural and historical background that are intricately linked. Though perceived by various human rights groups as restricting political opposition and criticism of the government,[5] the Singapore government continue to use the Internal Security Act (ISA) where necessary to counter any potential communal, religious and terrorism threats to the present day.[6]